mindmap

root((Frequentist

Hypothesis

Testings

))

Simulation Based<br/>Tests

Classical<br/>Tests

(Chapter 1: <br/>Tests for One<br/>Continuous<br/>Population Mean)

(Chapter 2: <br/>Tests for Two<br/>Continuous<br/>Population Means)

(Chapter 3: <br/>ANOVA-related <br/>Tests for<br/>k Continuous<br/>Population Means)

{{Unbounded<br/>Responses}}

One<br/>Factor type<br/>Feature

)One way<br/>ANOVA(

Two<br/>Factor type<br/>Features

)Two way<br/>ANOVA(

4 ANOVA-related Tests for \(k\) Continuous Population Means

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain how analysis of variance (ANOVA) partitions total variation into between-group and within-group components.

- Interpret the meaning of the \(F\)-statistic and its role in testing mean differences across groups.

- Describe the difference between main effects and interaction effects in a two-way ANOVA.

- Identify potential interaction patterns via appropriate plotting when conducting a two-way ANOVA.

- Conduct one-way and two-way ANOVA in a reproducible manner using the hypothesis testing workflow via

RandPython. - Identify the assumptions underlying one-way and two-way ANOVA, including independence, normality, and homoscedasticity.

- Evaluate model diagnostics to assess whether ANOVA assumptions are met.

It is time to expand our hypothesis testing framework from comparing two population means to a generalized approach for \(k\) population means by exploring analysis of variance (ANOVA). ANOVA is a foundational test in frequentist statistics designed to compare means across multiple populations under specific distributional assumptions, which we will examine in this chapter. Originally formalized by Ronald A. Fisher (Fisher 1925), ANOVA extends the concept of the two-sample \(t\)-test by partitioning the total variability of our outcome of interest into components attributable to main effects, interactions, and random error. This partitioning enables us to determine whether observed differences in groups are improbable to appear under the null hypothesis, which states that all groups share the same population mean.

Heads-up on some historical background in statistics!

While Ronald A. Fisher (1890–1962) is rightly recognized as a significant figure in modern statistics for developing key concepts such as ANOVA, it is imperative to recognize the broader context of his legacy. Beyond his pioneering contributions to statistics, Fisher was also a prominent advocate of eugenics, a movement that promoted pseudoscientific ideas about human heredity and social hierarchy. His involvement with the eugenics community is well documented (MacKenzie 1981). These views have been called out by certain members of the scientific community (Tarran 2020). That said, we (the authors of this mini-book) consider that students and scholars need to distinguish Fisher’s statistical insights from the unethical ideologies he supported, while also acknowledging the social responsibility to critique the historical misuse of science.

Fisher’s statistical work remains central to frequentist inference. However, educators and researchers must confront the historical connection between statistical innovation and eugenic thinking in early 20th-century science (Tabery and Sarkar 2015). By explicitly addressing this context, we can acknowledge the rigour of Fisher’s methodological contributions while rejecting the discriminatory worldviews he promoted. This approach aligns with contemporary efforts to ensure that teaching statistics is grounded not only in subject matter accuracy but also in ethical reflection and historical accountability (Kennedy-Shaffer 2024).

This chapter builds on the concepts introduced in the earlier works by Chapter 2 and Chapter 3, which concentrated on hypothesis testing for one and two groups, respectively. While those chapters primarily addressed pairwise comparisons, we will now shift our focus multiple comparisons:

- The one-way ANOVA, discussed in Section 4.2, will assume a single categorical factor with \(k\) levels. This approach allows us to test whether at least one group mean is significantly different from the others.

- In contrast, the two-way ANOVA, from Section 4.3, will incorporate an additional categorical factor with \(m\) levels, permitting the analysis of both main effects and interaction effects. Interaction terms in ANOVA are especially useful for revealing cases where the effect of one factor depends on the level of another, a situation often encountered in complex experimental designs.

As a side note, the workflow guiding this chapter, as referenced in Figure 1.1, will provide a structured approach for applying both one-way and two-way ANOVA to the same A/B/n dataset (see Section 4.1).

Heads-up on the importance of ANOVA in data science!

In modern data science, ANOVA remains significant, particularly in A/B/n testing (the generalization of A/B testing to multiple treatments). This approach allows for the simultaneous evaluation of various treatment variations or designs. ANOVA is valued for its interpretability and its flexibility in handling both balanced designs (where there is an equal number of replicates for each experimental treatment) and unbalanced designs (where there are unequal numbers of replicates). These strengths have solidified its role in both academic research and practical applications.

4.1 The ANOVA Dataset

The simulated dataset discussed in this chapter relates to an experimental context known as A/B/n testing, which is an expansion of traditional A/B testing as previously discussed. In a typical A/B testing, participants are randomly assigned to one of two strategies, referred to as treatments: treatment \(A\) (the control treatment) and treatment \(B\) (the experimental treatment). This approach enables us to infer causation concerning the following inquiry:

Will changing from treatment \(A\) to treatment \(B\) cause my outcome of interest, \(Y\), to increase (or decrease, if that is the case)?

In an ANOVA setting, the outcome must be continuous. The primary goal of A/B testing is to determine whether there is a statistically significant difference between treatments \(A\) and \(B\) concerning the outcome. Additionally, because we are conducting a proper randomized experiment, we can infer causation (which goes further than mere association), as treatment randomization enables us to get rid of the effect of further confounders.

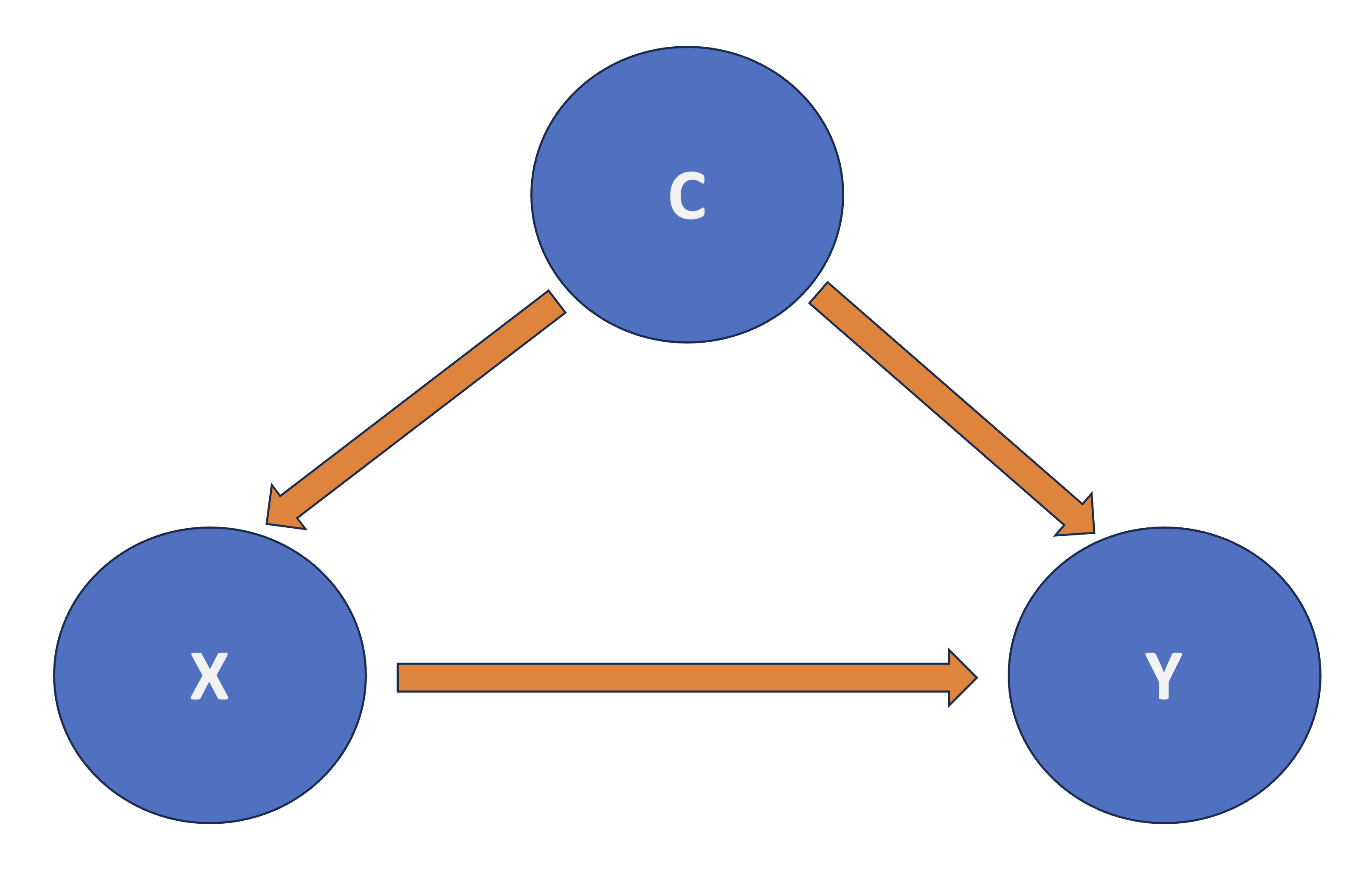

Heads-up on confounding!

In causal inference, confounding refers to the mixing of effects between the outcome of interest, denoted as \(Y\), the randomized factor \(X\) (which is a two-level factor in A/B testing, corresponding to treatment \(A\) and treatment \(B\)), and a third, uncontrollable factor known as the confounder \(C\). This confounder is associated with the factor \(X\) and independently affects the outcome \(Y\), as shown by Figure 4.2.

When conducting experiments with more than two treatments in A/B testing, the experiment is referred to as A/B/n testing. In this case, the “n” does not indicate the sample size; rather, it simply represents any number of additional treatments beyond treatments \(A\) and \(B\). With this clarification, we can now proceed with our simulated dataset.